Associate Professor Catherine Cox and Professor Hilary Marland

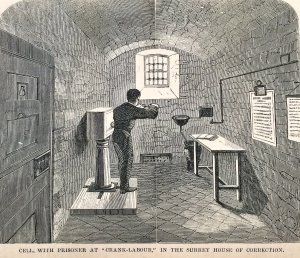

Time and again as prisoners were moved to their cells to commence their term of separate confinement they described the cell’s measurements, proportions and appearance, and their dread at entering it, ‘the closing of the door behind them a finality that betokened a dreadful new beginning’.[1] Austin Bidwell examined his cell with ‘curiosity and consternation’ as the realisation took hold that ‘for long years that little box – eight feet six inches in length, seven feet in height and five feet in width… would be my only home’.[2] Though Frederick Brocklehurst only spent a month in prison, the entire time in solitary confinement, he produced a graphic account of his life in Strangeways in a ‘white-washed cube, 7 feet by 8 by 13, with a barred window of ground glass at one end, and a black-painted iron door at the other’. ‘After a time he is reduced to the level of a wild animal in a menagerie, pacing his cage, merely existing between meal hours’.[3]

Cellular Isolation

Under the new regime of separate confinement, introduced at Pentonville, London in 1842 and later transported across the British Isles and much of the western world, cellular isolation was initially to be endured for 18 months, during which time the convict had no contact with other prisoners, was to conduct himself in silence on pain of punishment, and was – aside from the cell visits of the chaplain and other prison officers – alone with his own thoughts and fears. The convict was to work, eat and sleep in the cell, removed only for brief visits to attend chapel and to exercise. All the convict required to exist was contained in this bare space – a tin bowl and mug, a hammock or plank bed, a chamber pot, work materials and the Bible. Convicts quickly learned the daily routine that never varied:

It is six o’clock; I arise and dress in the dark; I put up my hammock and wait for breakfast… I take a tin plate and tin mug in my hands and stand before the cell door. Presently the door opens; a brown, whole-meal, six-ounce loaf is place upon the plate; a tin mug is taken, and three-quarters of a pint of gruel is measured in my presence, when the mug is handed back in silence, and the door is closed and locked. After I have taken a few mouthfuls of bread I begin to scrub my cell. A bell rings and my door is again unlocked. No word is spoken, because I know exactly what to do. I leave my cell and fall into single file… All of us are alike in knowing what we have to do, and we march away silently to Divine service. We are criminals under punishment, and our keepers march us like dumb cattle to the worship of God.[4]

Reflection and Reform

The cell was the key component of the system of separate confinement, intended to produce reflection and reform, to throw prisoners back on their own thoughts, recollections and regrets until they were ready to declare their repentance for past sins and crimes, clearing the path for their deep-seated reformation:

In the stillness and solitude of his cell the long-forgotten religious precept, the early domestic admonition and example, the last solemn warning of the dying parent, the traces early impressed upon the youthful memory, all arise before the guilty conscience with a vividness and force to which the solemnity of the occasion gives tremendous emphasis. All artificial supports are now withdrawn, and the culprit is made to feel the reality of his condition, and the fearfulness of that prospect leads him to think of ‘righteousness, temperance, and judgment to come’.[5]

Dread and Anxiety

However, more often the cell triggered dread and anxiety. The separate cellular system appealed to the prison authorities on punitive as well as reformatory grounds, and, as the Reverend Joseph Kingsmill at Pentonville Prison suggested, solitary confinement was ‘calculated to strike more terror into the minds of the lowest and vilest class of criminals than any other [system] hitherto devised’.[6] Pentonville, with its 18-foot perimeter wall, was intended to produce isolation within the prison and from the outside world. Along its hallways, with three levels of solitary cells, the doors were arranged so that the prison officers could not be seen by the prisoners, though they themselves could be watched at all times. The convicts were allowed one 15-minute visit every 6 months, and permitted to write and receive two letters each year. By 1850 it was reported that some 11,000 purpose-built separate cells had been built or were nearing completion in England and 55 separate cellular prisons.[7] There were many more male than female convicts serving their time in separation throughout the convict system, and women typically spent less time in separate confinement. In Mountjoy Female Prison in Dublin the female prisoners spent 4 months in isolation.

The Risks of the Cell

Even in the early years of the new separate system, concerns were provoked about the power and the risks of the cell. The chaplain of Spike Island Prison in Cork, Reverend Charles Gibson, described the cellular prison as ‘a delicate piece of machinery which no unskilful hand should touch. A few more turns of the screw, and you injure both the body and mind of the prisoners.’[8] Chaplain Kingsmill at Pentonville became convinced as more and more prisoners showed signs of mental disturbance that separate cellular confinement was not working as it was intended to and gradually the Pentonville regime was made less severe, and the length of separation reduced to 9 months by 1853. A reduced period of 8 months in separation was in operation at Mountjoy Prison by 1854. Henry Martin Hitchins, Inspector for Government Prisons in Ireland, had dismissed the Pentonville regime as ‘too severe’, yet he remained convinced of effectiveness of the ‘dread’ felt by the convicts returning to his ‘separate cell’.[9]

The separate system, as originally devised in the 1840s, would be repeatedly modified during the nineteenth century. However the system of cellular isolation and confinement in cells for up to 23 hours a day would remain a feature of the prison system well until the twentieth-first century – in recent decades due to under-resourcing rather than any faith in the reformative power of the cell – despite repeated evidence of the risks to the mental well being of the prisoners.

Notes

[1] Philip Priestley, Victorian Prison Lives: English Prison Biography, 1830-1914 (1985), p.39.

[2] Austin Bidwell, From Wall Street to Newgate (1895), p.397.

[3] F. Brocklehurst, I was in Prison (1898), p.xvii.

[4] Florence Elizabeth Maybrick, Mrs. Maybrick’s Own Story: My Fifteen Lost Years (1905), pp.68-9.

[5] Third Report of the Inspectors of Prisons of Great Britain, Part 1, 1837-38, p.16.

[6] Reverend Joseph Kingsmill, Chapters on Prisons and Prisoners, 3rd edn (1854), p.116.

[7] William James Forsythe, The Reform of Prisoners 1830-1900 (1987), p.45.

[8] Charles Bernard Gibson, Life among Convicts, 2 vols (1863), vol. 1, p.69.

[9] National Archives of Ireland, Government Prison Office, Letter Books, GPO/LB/12, 7 July 1849–14 Dec 1851, p.53.