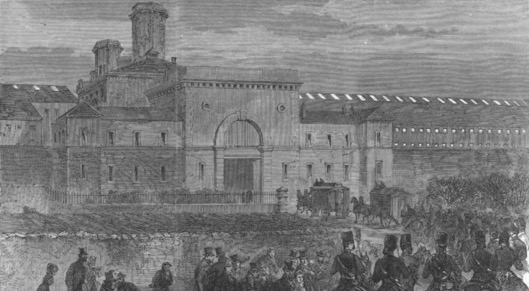

Mountjoy Prison, Dublin 1850

The introduction of separate confinement to Mountjoy Convict Prison, Dublin

Associate Professor Catherine Cox

Sir Walter Crofton (1815–1897), prison administrator and penal reformer, looms large in studies of Ireland’s history of the criminal justice system. He is characterised as the key figure in shaping penal policy in Ireland in the later nineteenth century while his introduction of a variant of Captain Alexander Maconochie’s ‘progressive stages’, known as the ‘Irish system’, to Irish convict prisons is often eulogized.[1] Crofton’s dominance over the Irish criminal justice system emerged in the mid-1850s and came after the opening of Ireland’s ‘flagship’ penal institution, Mountjoy model prison, which received it first prisoners in 1850. Originally opened with 450 single occupancy cells for male prisoners, it was devised and designed for the introduction of the new ‘Philadelphia’ system of separate confinement associated with Pentonville ‘Model’ Prison (1842) in England and with the Eastern State Penitentiary in Philadelphia (1829).

The role of Henry Martin Hitchins, Inspector for Government Prisons in Ireland

The responsibility for overseeing the opening of Mountjoy, and for devising a modified version of separate confinement for the modern prison system in Ireland, fell to Henry Martin Hitchins, the then Inspector for Government Prisons in Ireland. Hitchins, who had been first employed at the Chief Secretary’s Office in 1826, was appointed as Inspector of Irish Government Prisons in 1847.[2] Hitchins’ opinions on the separate system, the bedrock of mid-nineteenth-century penal policy and of the ‘modern’ prison, are detailed in a series of Government Prisons Office Letter Books held in the National Archives of Ireland. Hitchins’ letters on the separate system and its implementation at Mountjoy prison are remarkably open, frank, and revealing of his opinion of the official penal policy.

Hitchins visit to Pentonville prison

In preparation for the introduction of the separate system to Mountjoy, Hitchins visited Pentonville Prison in January 1850, three years after the deaths of William Crawford and Reverend Whitworth Russell, the key advocates of the regime. He observed the prison ‘at all hours, and in all stages of its discipline’, and, in his subsequent report on his visit, he noted modifications that were to be made at Pentonville to the ‘purest’ form of separate confinement. In particular, he noted the almost universal rejection of the 12-15 month period of confinement ‘as too severe, affecting both the mental and physical condition of the convict and tending to stupefy’. In his report, Hitchins was especially critical of the emphasis placed on religious instruction, dismissing it as a ‘dead failure’. The chapel seats at Pentonville, he noted, ‘disfigured by grotesque carving and gross inscription, attest the diligence if not the piety of the inmates’. For Hitchins, ‘the great moral results of separate confinement’ were ‘quite lost in a maze of petty regulation’. Hitchins concluded that “separation should be the principle” upon which Mountjoy prison is to be conducted, yet that many details of Pentonville which being extreme are necessarily futile, may be safely avoided’.[3]

A ‘pure’ form of separate confinement

Convinced of the dangers of the ‘purest’ form of separate confinement, Hitchins set about devising a modified version. The strengths of the regime, he argued, were its capacity to act as a deterrent – the ‘dread’ of the convict returning to the separate cell – and as a mechanism for enforcing education and industrious habits. Hitchins insisted that these elements of the regime should be promoted at Mountjoy, while the influence of the chaplain was circumcised. Chaplains were ‘to visit convicts in cell for conversation every day and visit school classes’ but they were forbidden from exercising ‘direct control over the School master’ who, in turn, was to confine himself to secular education. This was especially important in Ireland where ‘charges of proselytising’ complicated all matters relating to religious instructions. The emphasis was placed on training, either through convict labour or through reading. As Hitchins observed, success of the separate system ‘mainly depends on the minds of the prisoners being fully occupied.’[4]

The separate system and insanity

At the time of his visit to Pentonville, Hitchins was fully aware of the links being made between separate system and insanity. In February 1850 he firmly advised the medical officer at Mountjoy, Dr Francis Rynd, that the ‘examination [of prisoners] should not … be confined to physical defects only … but should also be extended to those other circumstances which might under the course of discipline to be adopted effect their “mental” as well as their physical condition.’[5] As Hitchins noted, ‘the objections which have been urged against this system … appear to be principally directed to the injurious tendency of [a] long period of separate confinement to produce a general debility of mind and body’. He identified three categories of prisoners at the greatest risk of succumbing to ‘utter prostration of the mental powers’ or ‘imbecility’. These were prisoners whose ‘prevailing character … is that of sullenness’ or in whom ‘insanity is hereditary’; those with ‘insufficient capacity to acquire trade, or receive other instruction’ and prisoners displaying a ‘tendency is to dwell unhealthily on any one subject, to the exclusion of all others.’[6] He was also cognisant of the dangers of removing convicts directly from separate confinement to transportation.[7]

The danger of moral contamination

Robert Netterville, the then Governor at Mountjoy Prison was tasked with implementing Hitchins’ modified system but Hitchins was dissatisfied with Netterville’s performance. Following his inspection of Mountjoy in July 1850, Hitchins criticised Netterville for not ensuring that the system of separation pervaded the whole regime. While prisoners were each provided with a separate cell, their employment in groups at outdoor work for the maintenance of their health had resulted, Hitchins asserted, in ‘association’ and the danger of moral contamination among the prisoners loomed. He insisted that ‘no prisoners must [sic] be placed in such a structure as to afford him an opportunity of communicating verbally or by eyes’. He also felt that the prison officers were too lenient and reminded Netterville that

prisoners committed to your charge have been convicted of grave offences against God and man, that they have forfeited their civil rights and are confined much to protect society against their evil practices as to afford them an opportunity of repentance and reformation. It is therefore of primary importance that the prisoners should be brought to a proper sense of their condition and after the religious exhortations of the chaplains nothing so directly tends to effect this object as a firm and steady exercise of a severe discipline.

For Hitchins, changes in prisoners’ behaviour were produced by ‘physical suffering’ and the strict adoption of severe discipline was necessary for success and reformation.[8]

The establishment of the Directors of Convict Prisons in Ireland

By 1854, the Irish Prison Commissioners concluded that the implementation of the separate system at Mountjoy had ‘varied considerably’ over the first four years. Then a parliamentary inquiry into the management and discipline of Irish convict prisons, prompted by the cessation of transportation and the introduction of penal servitude, expressed concerns over the variations in the Mountjoy disciplinary regime and the emphasis placed on profitable labour. They insisted that the primary purpose of separate confinement, ‘moral and religious improvement’, be re-asserted.[9] The findings of the 1854 parliamentary inquiry coincided with a scandal surrounding Hitchins’ inept management of the transportation of a group of convicts who, contrary to policy, were sent directly from Mountjoy to Australia. After months in solitary confinement, the convicts, some of whom were convicted during the Famine, experienced difficulties in adjusting to the greater levels of freedom while some were found to be incapable of work.[10] Hitchins was forced into retirement. He was forty-four years old.[11] The parliamentary inquiry also prompted the establishment of the Directors of Convict Prisons in Ireland in that year, with Sir Walter Crofton as chairman.[12]

Image

Illustrated London News

Notes

[1] L. Goldman, ‘Crofton, Sir Walter Frederick (1815–1897)’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 2004. [http://www.oxforddnb.com/view/article/65325, accessed 5 March 2017]

[2] T. Carey, Mountjoy. The Story of a Prison (Dublin, 2000), p. 52.

[3] National Archives of Ireland (NAI), Government Prison Office (GPO)/Letter Book (LB)/12/ 7 July 1849 – 14 Dec 1851, p. 53.

[4] NAI, GPO/LB/12, p. 63.

[5] NAI, GPO/LB/12, p. 35.

[6] NAI, GPO/LB/12, p. 36.

[7] NAI, GPO/LB/12, p. 235.

[8] NAI, GPO/LB/12, p. 128-133.

[9] Ibid., p.18.

[10] Carey, Mountjoy, 60.

[11] Freeman’s Journal, 2 Feb 1855.

[12] P. Carroll-Burke, Colonial Discipline. The Making of the Irish Convict System, (Dublin, 2000), pp. 97-102.

One Comment Add yours